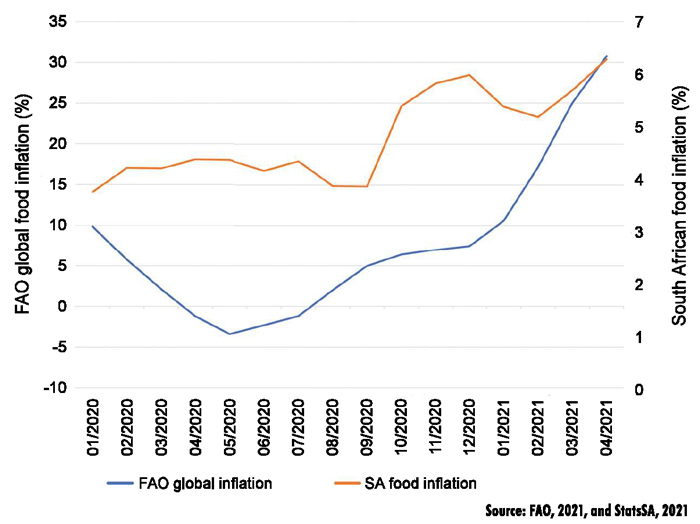

The global Food Price Index of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) increased by 30,8% compared to the corresponding time last year (Graph 1). This article explores the underlying drivers of global and local food inflation, and gives expectations on where it could go towards the end of the year.

Grains, oilseeds and associated products

Increases in grain and oilseed prices and the price of derived retail products is an ongoing global phenomenon since mid-2020. Several factors created an environment for this price surge.

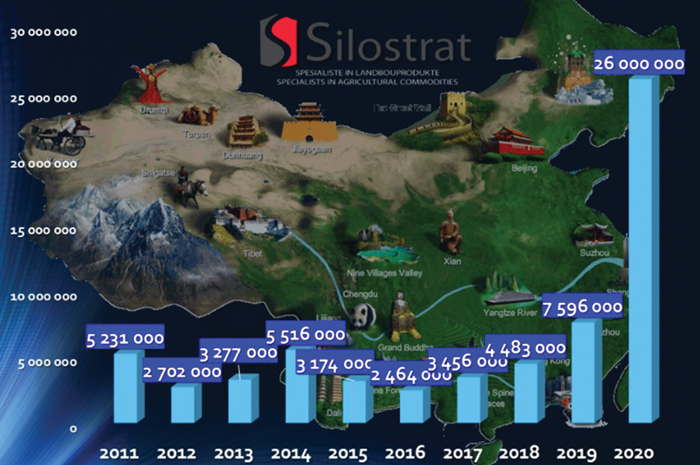

The first is a strong demand from China for feed grains such as maize, as depicted in Figure 1. This is a symptom of aggressive swine herd rebuilding after the devasting outbreak of African swine fever in 2018 and was exacerbated by several supply issues.

Most notable was the dry conditions in Brazil which caused the second maize crop, also known as the Safrinah crop, to be about 7% smaller than originally anticipated. Recent dry conditions in the United States of America (USA) also posed some threats to grain-planting progress in April and early May. However, this fear seemed to have abated with planting progressing faster than the historical average as May progressed.

In terms of oilseeds and vegetable oils, prices also surged due to a strong demand especially from China, but here there were more pronounced supply shocks. Labour disruptions associated with COVID-19 affected palm oil production whilst dry conditions in the Black Sea region pushed sunflower seed and oil prices higher.

These global forces pulled South African export parity prices higher and despite the projected local bumper crop, prices are roughly 20% higher compared to last year. However, a factor that has mitigated some of the rapid increases in global prices is the resilience of the rand, with the rand being roughly 23% stronger compared to the corresponding time last year.

Meat

Global meat prices have also increased over the past seven months, but the increase has been less pronounced than increases in grains, oilseeds and its related products. This is expected to be a consequence of pressures on the disposable income due to COVID-19 and its associated lockdowns.

As the world emerges from the pandemic, consumers have pent up savings and governments are providing huge stimulus packages. Global meat prices are responding to this. Locally meat prices have been increasing despite continued consumer pressures, especially in the case of red meat and pork.

In terms of red meat, tight supplies and high input costs have resulted in higher prices. Here an increased income from grains is allowing producers with dual livestock and grain enterprises to rebuild their herds more aggressively. Pork prices, in turn, have found price support from strong local and export demand. It is expected that this is due to the good value for money that pork products give, and these products are attractive for consumers with a constrained income.

Chicken prices, however, have not shown price rises corresponding to that of red meat and pork. This could be because the less affluent part of the population, which is reliant on chicken meat as a source of protein, is under more economic pressure and as a result, those producers are struggling to pass through the significant increases in input cost that have been apparent over the past months. It is expected that local meat prices will remain firm over the coming months.

Fresh produce

Locally, fresh produce inflation has shown divergent trends over the past month, with vegetables recording an inflation rate of 6,7% and fruit inflation being 0%. Vegetable inflation was predominantly driven by surges in tomato prices, which reached record prices in early April. This was due to extremely low volumes as a result of the heavy rains earlier in 2021. This negatively affected production volumes from the northern regions of South Africa.

Fruit, in turn, did not record inflation between April 2020 and April 2021. This is attributable to the high base of fruit prices in April 2020. During this month, the exchange rate weakened to close to R19 to the dollar due to the spread of the pandemic in South Africa and around the world, and the downgrade of South Africa’s sovereign credit rating.

This greatly supported the export realisation for fruits destined for the export market, but also resulted in local prices being high. Therefore, fruit prices are still firm but the rate at which they increased over the past year was recorded at 0%.

Fruit inflation is expected to turn negative over the rest of the year. Vegetable inflation could, however, stay relatively high. As a case in point, onion producers note that onion volumes will be lower over the coming months due to a cooler and wetter summer, which is expected to have a negative impact on the yield.

Dairy products

Global dairy product prices are up by 24,1% compared to a year ago and have increased for the eleventh consecutive month in April. This is underpinned by a strong demand, especially from Asia. As with global meat prices, dairy prices are benefitting from expansionary policies as the world emerges from the pandemic. Higher global prices are spilling over into local markets and combined with higher input costs, of which feed is the most notable, local dairy prices have increased substantially since last year.

Other products usually discussed with dairy in an inflationary context are eggs. Egg prices have also increased on the back of high feed costs. Here a concerning development is the recent outbreaks of avian influenza. If a spread such as the one in 2017 is to be repeated, supplies would be severely constrained and prices could surge. It is expected that inflation in dairy products and eggs will remain firm on the back of high input costs and a strong demand as an affordable source of protein.

Expectations going forward

A mitigating factor that has kept increases in local grain and oilseed prices modest, compared to the rest of the globe, is the resilience of the rand. Combined with this, it does seem that global prices, although still firm, have lost momentum and could decrease further as the size of grain and oilseed production for the current season in the Northern Hemisphere becomes known.

It is expected that this will also reflect in local grain and related retail products. This could further alleviate some of the input cost pressures that are contributing to inflation, specifically in livestock and dairy production. Analysts also expect that the rand could strengthen further due to international factors, but also due to South Africa’s favourable terms of trade.

Given this, we expect inflation to decrease from its current levels as we approach the end of the year. However, an increase in manufacturing and distribution costs could counter this, and developments in oil prices and other administered prices should be closely monitored to anticipate this.