The price of dry beans has got the bean story buzzing in the Ngaka Modiri Molema District, seeing that a 10-hectare piece of land can now bring about a total income of R187 000 – making small-scale farming “attractive”. The above is true when all else is in place: The crop is of a good quality, good grade and is delivered to a reputable market or an off-taker that pays.

Before you can produce any number of tons of any crop per hectare, you need to understand the crop needs, its behaviour in the environment and the response to different management systems.

Climatic requirements

TEMPERATURE

Dry beans is an annual crop that is well adapted to the warm season. The optimum growing temperature is between 18°C and 24°C. After the crop has emerged, day temperatures below 20°C will retard the growth of the plant.

After flowering, low temperatures lead to the formation of pods without seeds. The minimum frost-free period required for the different cultivars can vary between 85 and 120 days. Higher temperatures (above 30°C) during the flowering stage lead to the abscission of flowers and poor pod set, thus resulting in a reduced yield.

RAINFALL

During the growing season, dry beans use approximately 400 mm of water, which is less than what maize needs. This makes dry beans a good crop to grow if irrigation water is limited or if used as part of a crop rotation system to reduce overall irrigation needs.

Dry beans is a shallow-rooted crop, with the majority of roots found in the top 450 mm of the soil profile. Roots can grow deeper into the soil profile to get water, but this usually occurs late in the growing season when the plants begin to mature. For rainfed conditions an annual rainfall of 650 to 750 mm is ideal, with a minimum of 400 to 450 mm required in the growing season.

Drought prior to the flowering stage leads to poor growth and a low yield potential. The greatest need for water is during the flowering and pot-set stages. A dry period is usually followed by high temperatures, which lead to the abscission of flowers and pods during the flowering stage.

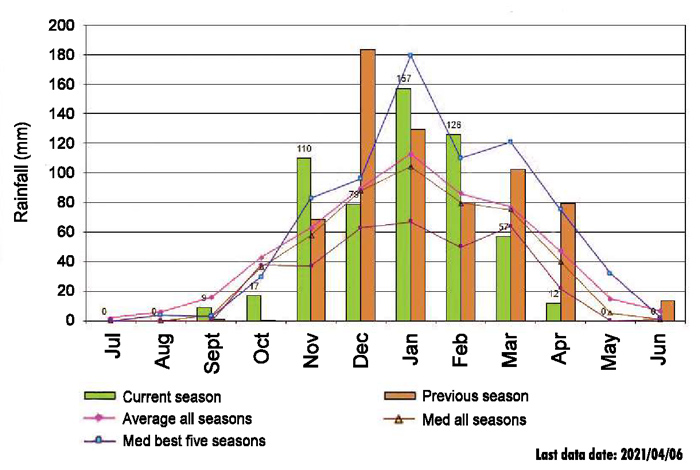

In the 2019/2020 season some of the producers who planted small white beans in the area realised between 1,5 tons/ha to 2 tons/ha as compared to the 2020/2021 season, when it was a struggle for a producer who previously harvested 1,8 tons/ha to reach 1 ton/ha.

The cumulative rainfall recorded between January and April was 390 mm for 2020 and 352 mm for 2021 respectively. The two figures do not differ much to cause such a significant difference in yield. Graph 1 demonstrates the distribution of the rain between these periods, which is critical for the crop and could have had an effect on the yield.

Soil requirements and cultivation guidelines

Dry beans prefer well-drained soil with relatively good fertility. Avoid planting dry beans in a field that floods easily, is heavily compacted or regularly develops a thick crust.

As with any crop, before selecting fields in which to plant dry beans, it is advisable to test the soil fertility first. Seedbed preparation for the planting of dry beans follows the same pattern as that for any field crop. The seedbed must be deep, level and firm, as this ensures better surface contact between the seed and the soil, increasing the absorption of moisture. A level seedbed also facilitates uniform planting and easier mechanical harvesting of the crop.

Undecomposed crop residue at planting time increases the danger of root diseases. It is highly recommended that crop residues should be worked into the soil earlier to reduce complications when planting the beans. Beans prefer an optimum soil pH (H2O) of 5,8 to 6,5, and are very sensitive to acidic (pH (H2O) < 5,2) soils. They will also not grow well in soils that are compacted, too alkaline or poorly drained.

Fertiliser requirements

Many legumes have the ability to fix nitrogen (N) from the air without the use of commercial fertilisers if inoculated with N-fixing bacteria. The N-fixing bacteria for dry beans is called Rhizobium phaseoli, and it is specific for dry beans. Inoculants used for soybeans or peas are different and will not infect dry-bean roots.

Unfortunately, the relationship between dry beans and Rhizobium phaseoli is not strong. Dry, hot weather, short periods of soil water saturation and cold weather all will result in the sloughing off of nodules, so achieving high dry-bean yields consistently using inoculation as a N source may be difficult.

Maximum bean yields cannot be obtained, unless an adequate and balanced quantity of plant nutrients is present. Where the soil cannot supply the elements necessary for high yields, commercial fertiliser should be used.

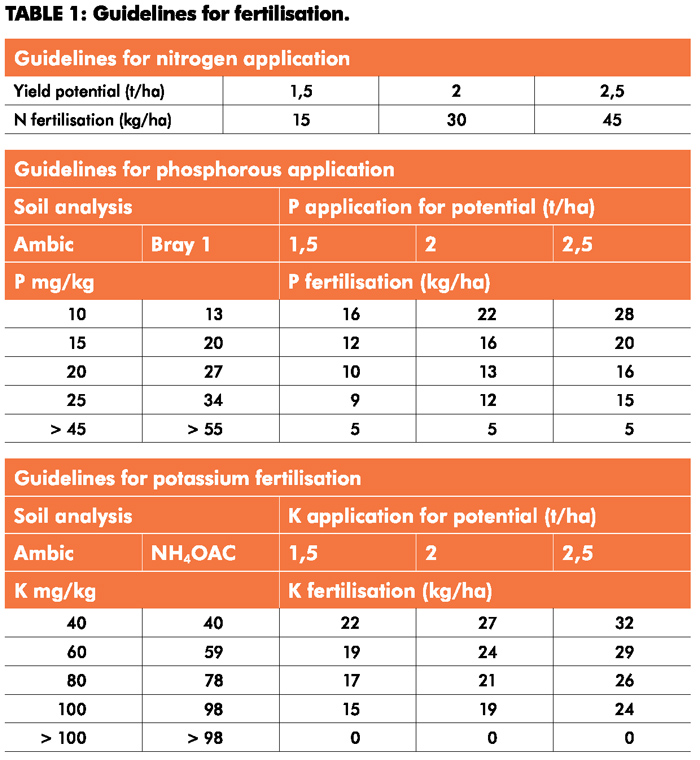

To determine the amount and kind of fertiliser needed, the soil should be tested for available soil nutrients. Fertiliser recommendations are based on the results of soil tests, previous cropping history, crop to be grown and expected yield per hectare (Table 1 – an extract of N requirements and the recommendation of phosphorus [P] and potassium [K] as per the soil analysis).

The recommended placement of fertilisers for beans is 5 cm to the side and 5 cm below the seed. The seed should not be in contact with the fertilisers, because bean seed is very easily injured when it comes in direct contact with fertiliser. Beans also do well with the application of foliar fertiliser to boost resilience.

The recommended placement of fertilisers for beans is 5 cm to the side and 5 cm below the seed. The seed should not be in contact with the fertilisers, because bean seed is very easily injured when it comes in direct contact with fertiliser. Beans also do well with the application of foliar fertiliser to boost resilience.

Weed control

Weeds may develop quickly in dry beans because the beans are slow to establish a canopy and do not compete well. Post-emergence weed control can be accomplished with a selective herbicide, followed later by a tine-weeder, depending on the weather and soil conditions and amount of plant residue in the field.

Do not cultivate when the beans are starting to emerge, as bean seedlings are very fragile and can easily snap. Cultivation can be undertaken when plants are between 5 cm and 12 cm tall until canopy closure.

Bean taproots are easily torn from the ground during imprecise mechanical cultivation. To minimise damage to plants, beans should not be cultivated when they are wet or just after they have flowered.

Diseases

In some years, losses to bean growers from disease infestations can amount to several millions of rands. In general, losses caused by bean diseases can be kept to a minimum by following some cultural practices:

- Plant disease-resistant varieties when available.

- Use disease-free seed (certified seed is recommended).

- Practise at least a three-to-four-year crop rotation.

- Keep fields clean by ploughing under bean refuse.

- Avoid working in bean fields while they are wet.

- Treat the seed with recommended chemicals to prevent damping-off.

The incidence and intensity of diseases and pests can differ from year to year due to environmental factors. The severity level of diseases can change rapidly, with most fungal diseases only becoming visible ten to 20 days after infection. To prevent an outbreak, fields should be inspected regularly and sprayed with relevant chemicals.

Cost of production and income probabilities

The cost of production of beans for a specific tonnage will vary from area to area and amongst producers. Some production costs may be reduced by using seed that has been reserved from a previously harvested crop. However, this needs to be approached with careful consideration as they may carry diseases which could lead to low yields and an increased cost of disease control for the producer.

With the cost of production ranging from R9 500/ha to R13 000/ha for a crop ranging from 1 ton/ha to 2 tons/ha and with a price per ton of R12 500/ton – depending on the market – it figures that a producer can make between R12 500/ha and R25 000/ha, with gross profit margins of between 28% and 48%. The average to the upper end of the profit margin is achievable when all else has gone well during the production season.

Summary

With the margins being so lucrative, dry beans can be a good source of income for producers when the production requisites have been followed correctly and when He who provides the rain, brings it in a manner that supports the important growth stages.

As beans are so sensitive to a lack of water at crucial stages, even when the rainfall in the season meets the minimum amount of water required, it is advisable for producers to have a good proportional mix of crops to minimise the risk of a total loss of income during periods when the weather doesn’t play its part too well.

Always include crops that are more resistant to temporary water stress when planning your production. The follow-up crop in a rotation will always benefit from the legume, and vice versa, the legume from a previously well fertilised maize field.

References

- ARC-GCI, 2002. Dry-bean production manual

- Dry-bean production in the Lake and North-eastern States. Agriculture Handbook No. 285, Agricultural Research Service, USA Department of Agriculture

- FERTASA, 2016. Fertiliser Handbook

- NWK rainfall data, April 2021

- http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/crops/facts/90-058.html

- https://www.grainsa.co.za/boost-grain-production-with-legumes

- https://www.grainsa.co.za/know-the-value-of-dry-beans